Film studies mostly discuss content; Representations of gender, race, sexuality and such are at the center of the discourse for years. When it's not, we tend to discuss outdated business models, distribution or technologies. We are still fascinated by Bazin's theory that the camera captures everything in front of the lens as an act of magic, yet we are aware that VFX are deceiving our perception (years before generative artificial intelligence [GAI] do the same).

I think it is time to move on and understand that the way we consume media has rapidly and radically changed- remote controls, smart TVs, streaming, user interfaces, hidden algorithms and much more; They need to be part of the studies in the undergraduate level of film studies. I wasn't lucky enough to learn that in any of my academic courses, but explored a little bit of that by myself and wrote several of my seminars about that approach:

1. Quantitative analysis (theatrical window)

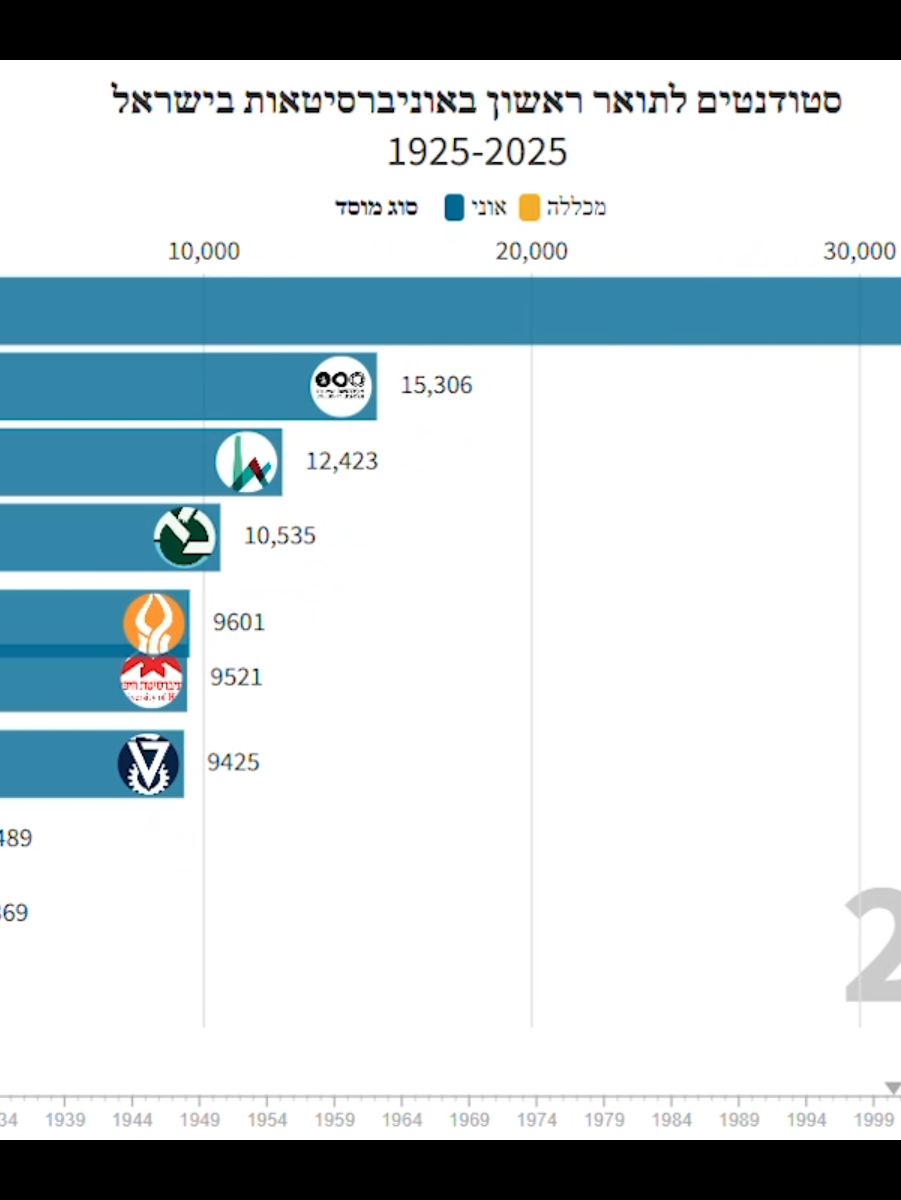

In a seminar paper from my graduate degree, I argued that we need to talk about film preservation. One reason is that it is almost impossible to keep up with the theatrical window (TW). The "theatrical window" is the time frame during which a film is shown in film theatres from the national premiere day of that theatre until the day it leaves and moves to its next step in its lifecycle (usually VOD and community screenings).

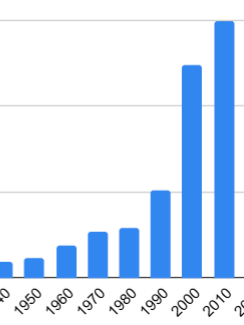

TW used to be longer in the past, lasting over 6 months, some sources say, in the 1990s. Of course, successful films get longer TW, trying to sell more tickets. The following table shows the TWs of the highest grossing films of the year between 1980-2024. We can see a decline in the length of the TW starting from the year 2000. The sources for the data are the websites Box Office Mojo (highest grossing film each year), and The Numbers (TW length in weeks).

This kind of analysis is rare in film studies in Israel. We don't gather data, put it in spreadsheets, compare it, look for a change, or suggesting reasons.

2. User interface analysis (Netflix home page)

We think that we have personal taste in art. "We don't just randomly watch a film. I like Almodovar, not Cassavetes", we say to ourselves. This might be right, but let's not belittle the importance of the Netflix screen composition. Look at the screenshot below. Above that top carousel, we see the poster of the film "Carry On". That poster is 32.5 times larger than the posters underneath it (6.5X wider; 5X taller), not to mention- placed above as a headline.

A second view at the picture reveals that "Carry On" appears also in the carousel. That means that Netflix dedicated lots of the home page space to that film. That film was purchased by Netflix as a film that would probably keep the clients satisfied. Their Adjusted Viewer Share (AVS) algorithm was designed to make sure that subscribers that consider canceling their subscription will stay. They feed us what they want us to watch to justify the acquisition. That way they can have only a small fraction of the whole history of cinema (we don't like to see " We don’t have ___ but you might like:").

That was just the tip of the iceberg in that topic. The lesson here is to ask new, technological questions like "How do they know me?", "What categories they offer me?", "Why does content evaporate at that specific time?", "If the streaming service will delete this film, where else can I see it legally?". The streaming services are going around the Paramount Decree that forbids production companies from owning film theatres. If you don't believe me, try to find "Bandersnatch" outside of pirate bay.

3. Cognitive experiments (MVP)

How long does it take to identify which film we are seeing? Imagine turning on your TV and trying to name the TV show in front of you. You'll be looking for clues- familiar faces, locations, known objects (like Breaking Bad's blue meth). It could be stylistic elements such as unique camera angles or special coloring. No matter what the show, it will take you a moment and you'll use your memory from past viewings.

We use our brains to compare geometry (type of faces, room compositions, object sizes…) or to process colors. We build expectations, detect lies and construct plots, all by using our brains. In the last 30 years there was an increase of contents that require rewatching, and content asking us to fill gaps while watching (Memento and Inception, e.g.)

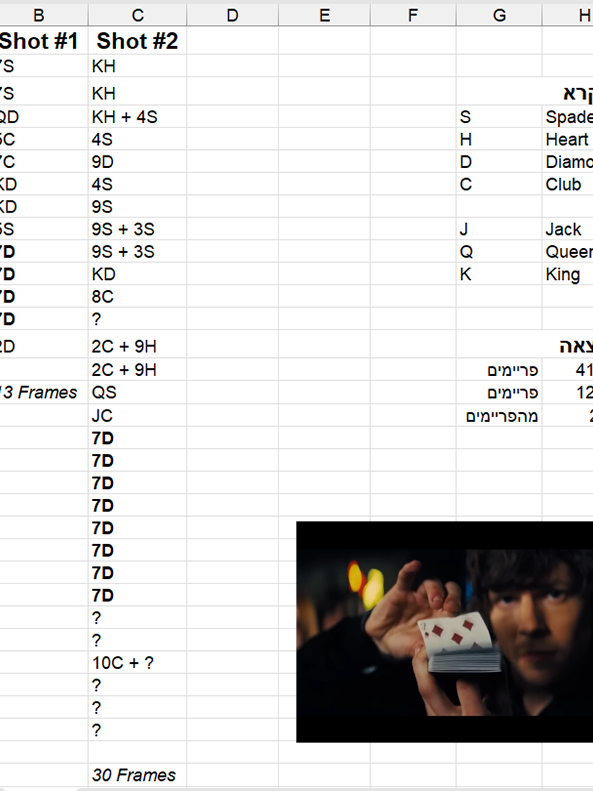

Old-school film theories cannot help us here. I had the great pleasure of studying a Cognitive Film Theories seminar taught by Dr. Gal Raz, an Israeli psychology and film scholar, who explores the connection between media and empathy. A year before that course, I listed all the films I had ever seen and started taking a frame from each of them. Shortly after I had a collection of few hundred frames that I assembled on a timeline, assigning each of them a 1/24th of a second of screen-time. Eventually I had a video of 800 frames. Each of the frames was the most representative frame for that film, in my opinion.

At the end of the semester, when I had to write my seminar, I immediately knew what it would be about- frame recognition. After a discussion with Dr. Raz, I let 25 people watch it separately and I asked them to name the films they saw. Later, they got a list of the films that appeared in the short film, which they needed to tick "V" if they ever saw it and another "V" if they thought they saw a frame of it in the short film.

The result reinforced "Miller's magic 7" rule, saying that participants will declare 7 objects, plus or minus 2 (meaning 5-9 films), and showed that animated characters painted with a minimal color-palette and highly saturated colors belonging to a broad franchise are most likely to be recognized by viewers; Characters like SpongeBob SquarePants & Patrick Star, Shrek and Winnie the Pooh were most recognized. Famous actors like Jonny Depp and Michael Jordan also received high score of recognition. In the case of the frames of Mike Myers' The Cat in the Hat & Mena Suvari's American Beauty, it is difficult to determine what in the combination made it ultra recognizable- the high red saturation, the distribution of the film, or the actors.

As far as I know, no student in the Tisch Film School has ever conducted an experiment this size or larger. We were never taught to examine films in this method. I am aware that some groups abroad use this method to survey a topic.

*This experiment was asked to be approved by the Faculty of Arts for conducting experiments and wasn't declined because it was not considered to be an experiment that needs any approval.

**The narrow selection of participants (mostly art students in their 20s) shows that these results are only guidelines and assumptions for further experiments. An attempt to get funding for bigger experiments was done and declined.

4. Designing solutions (HydroCinema)

We live in unique times when we can easily plug a cable into a hole in the wall and see electricity do its magic. For most of human history, entertainment was expensive, not to mention private entertainment. If someone wanted to watch the best actors performing Shakespeare in their yard, just with their F&F, they needed to be wealthy or royalty; today I can open my YT app and see them in the most private places, for free. No one guarantees that it will stay this way forever. Maybe in the future wasting electricity on entertainment will be something to be embarrassed at.

When the film projector was first shown to the world, it was hand-cranked. That means that a movie didn't have a fixed frame rate, therefore, no fixed time length. Edison made the frame rate fixed by his projector. From that point on, every frame projected used electricity! Even if the power grid uses solar, hydro, thermal or nuclear energy- it converted to electricity. All of those have their loss of energy by conversion.

It was a challenge for me to design the first film projector that runs only on the mechanical power of renewable energy. First, I must admit that I'm not an engineer of any kind. I'm not a good mechanic either, nor a draftsman, just a film enthusiast with crazy ideas. Second, I chose hydro power after learning a brief course about renewable energy.

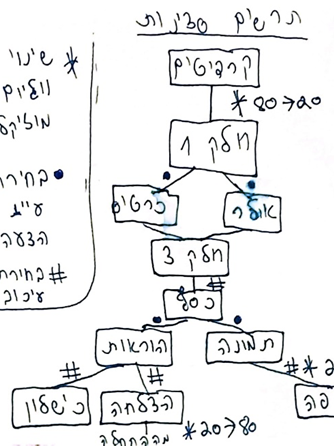

Hydro-power is the only renewable energy that is stable enough over a period of any given 2 hours. Solar energy cannot produce at night, a favorite time for film-watching; wind power is unpredictable and unstable; nuclear isn't safe next to an audience. Hydro-power can simply mean that a container of water is being flushed down for 2 hours to another container, and in between there will be a water wheel that will spin. That spin can transform into spinning the film-reel set (supplier and taker).

Of course, it has problems that I don't know how to solve right now- how to light the bulb in the projector; how to get the water back to the upper container afterwards; how to shoot films without electricity; how can we distribute TV and interactive media.

If this was a real project, someone would have provided the sharp minds needed. At this moment, a simple diagram, branded as "HydroCinema" is all we have. But look what else we have- attention to a new problem, a new theory about how our society is dependent on media, which is dependent on electricity. How often do you find a film/media scholar interested in electricity?

If this was a real project, someone would have provided the sharp minds needed. At this moment, a simple diagram, branded as "HydroCinema" is all we have. But look what else we have- attention to a new problem, a new theory about how our society is dependent on media, which is dependent on electricity. How often do you find a film/media scholar interested in electricity?